2022 County Health Rankings National Findings Report

Advancing a Just Recovery for Economic Security and Health

Executive Summary

County Health Rankings & Roadmaps (CHR&R) brings actionable data, evidence, guidance, and stories to diverse leaders and residents so people and communities can be healthier. The University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute created CHR&R for communities across the nation, with funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

This year, we focus on the importance of pursuing economic security for everyone and all communities. As we recover from the COVID-19 pandemic and the layered crises of racism and economic exclusion, we can work to assure that individuals, households, and communities can meet their essential needs with dignity and pursue opportunities for health. The pandemic both revealed and worsened the burdens and barriers that women, people of color, and people with low incomes face. It also underscored that resources have not been distributed fairly within and across communities.

Summary of Findings

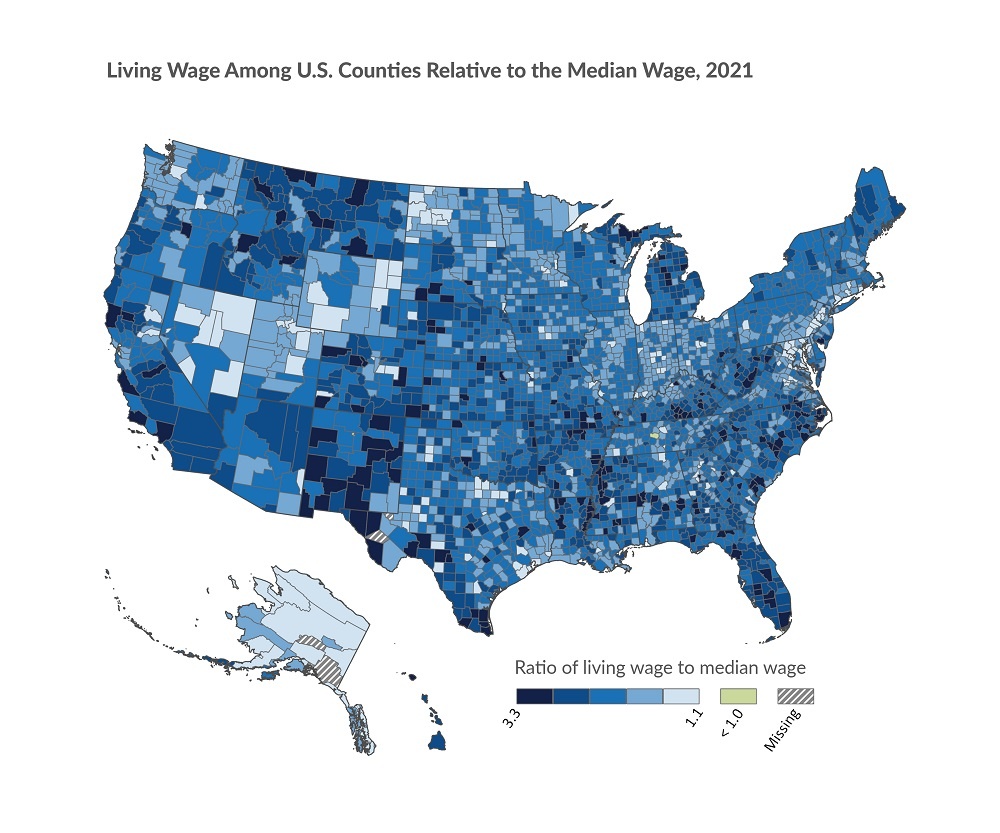

- Jobs must lift workers out of poverty, not keep them in it. Living wages cover basic needs and are essential to live a healthy life. Across U.S. counties, the average living wage is $35.80 an hour for a household with one adult and two children. Depending on location, the living wage dips to a minimum of $29.81 an hour and rises to a high of $65.45 an hour.

- Across the country, economic security is out of reach for many. A fair and just recovery means that everyone in a community can enjoy the promise of opportunity, but in nearly all U.S. counties, a typical worker’s wage is less than what would be considered a living wage for one adult with two children for the area. Among these counties, a more than 73% wage increase would be necessary to make a living wage, while some counties need as much as a 229% increase.

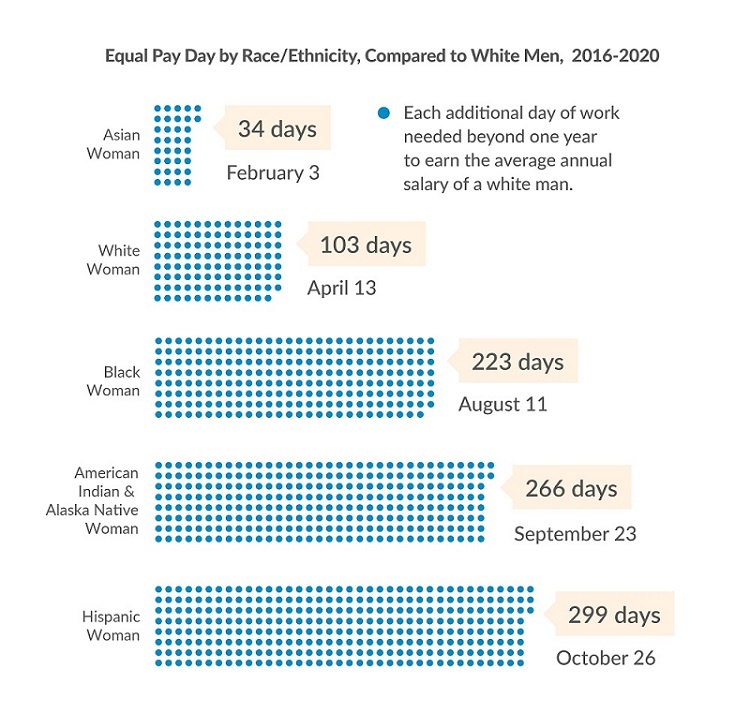

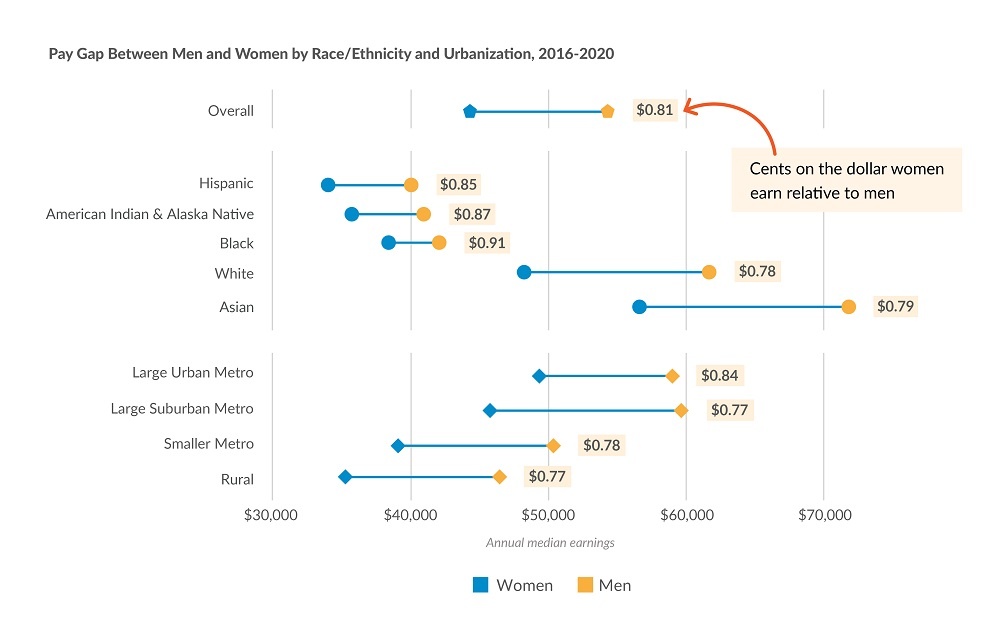

- For decades, working women, particularly women of color, have navigated employment discrimination, been segregated into female-dominated sectors such as service, education, and health care, and received less pay for equal work. Women earn little more than 80 cents on the dollar men earn, and by comparison, the earnings for women living in rural areas and women of color remain among the lowest. To earn the $61,807 average annual salary of a white man, women of all races and ethnicities must work several more days, if not months, into the following year. Hispanic women must work an additional 299 days or nearly 10 months. The pay gap between men and women, like other forms of income inequities, affects everyone in the community but is especially harmful to the health of working women responsible for covering basic needs and providing for those who depend on them. An economy that truly works for everyone includes equal pay in living wage jobs and work-family supports such as paid sick leave and paid family leave.

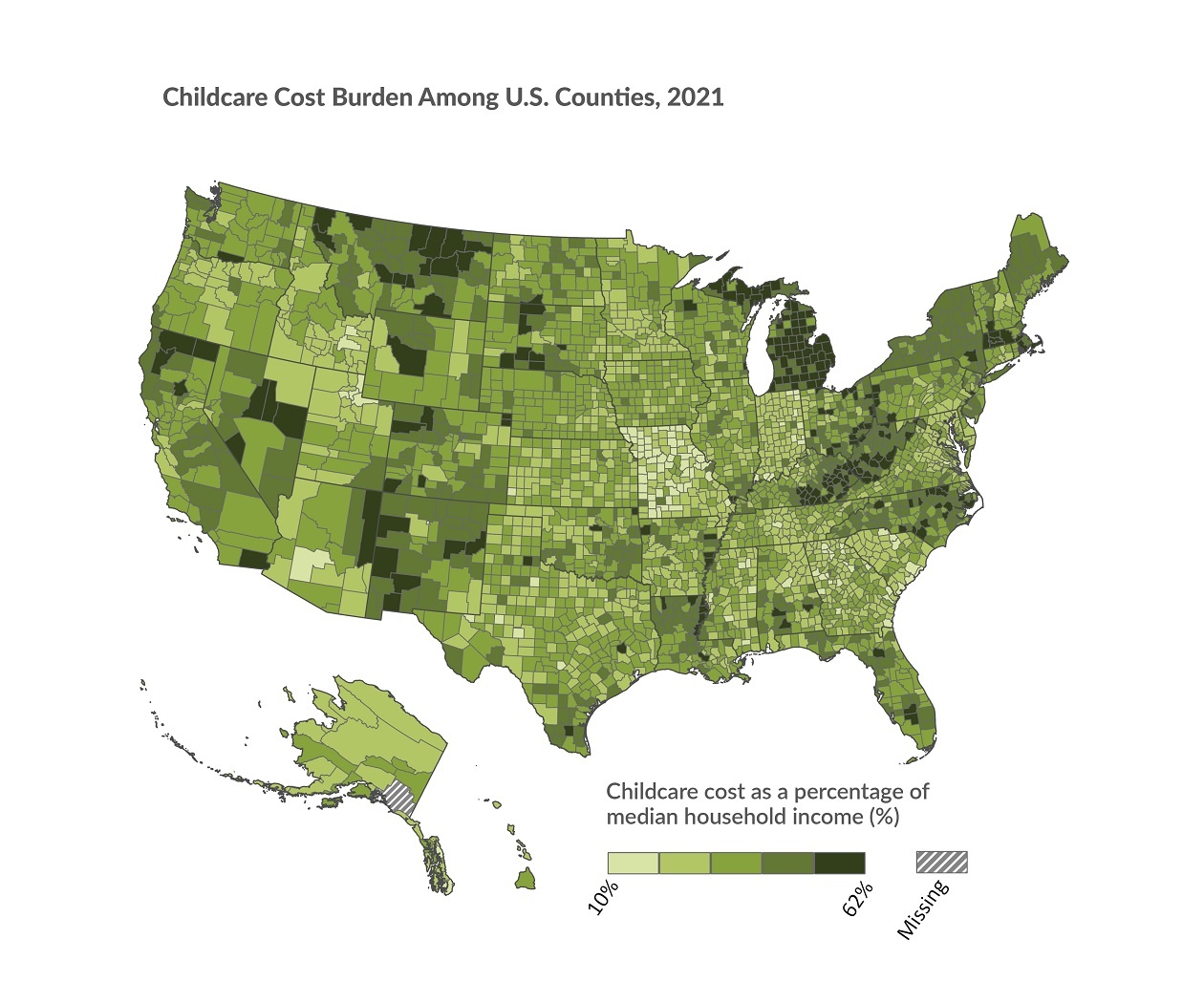

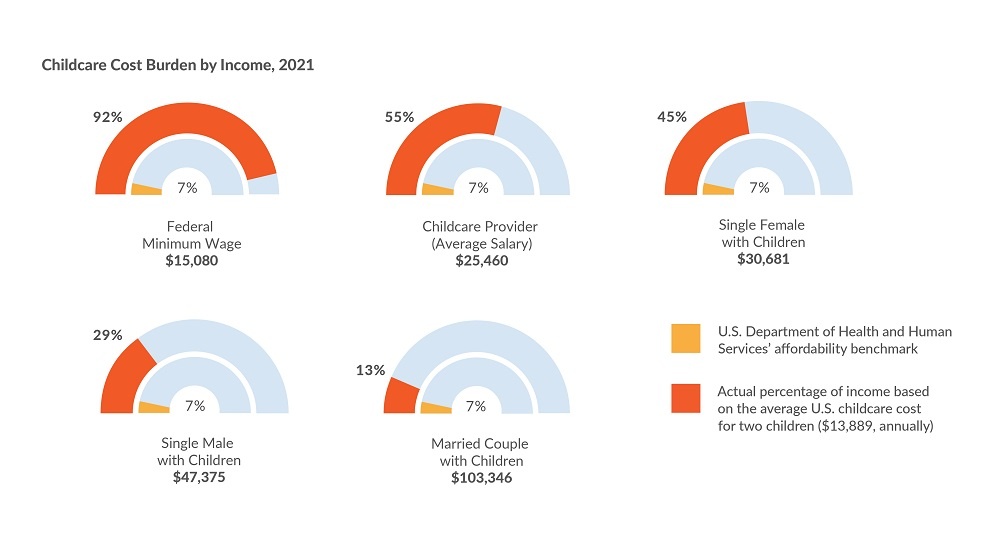

- Parents, caregivers, and communities need their children to have a safe and enriching place to learn and develop. The COVID-19 pandemic brought attention to the critical role accessible and affordable childcare, schools, and early learning centers play in our communities, allowing parents and caregivers to participate in the workforce. On average, across counties in the U.S., a household with two children spends 25% of its income on childcare, more than three times the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ 7% affordability benchmark. The burden of childcare costs is even greater for caregivers working low wage jobs. Across U.S. counties, a minimum wage worker (at the federal amount of $7.25 an hour) with two children would need to allocate nearly all (90%) of an annual paycheck towards the average cost of childcare. A robust and equitable recovery depends on expanding the availability of affordable, high-quality childcare.

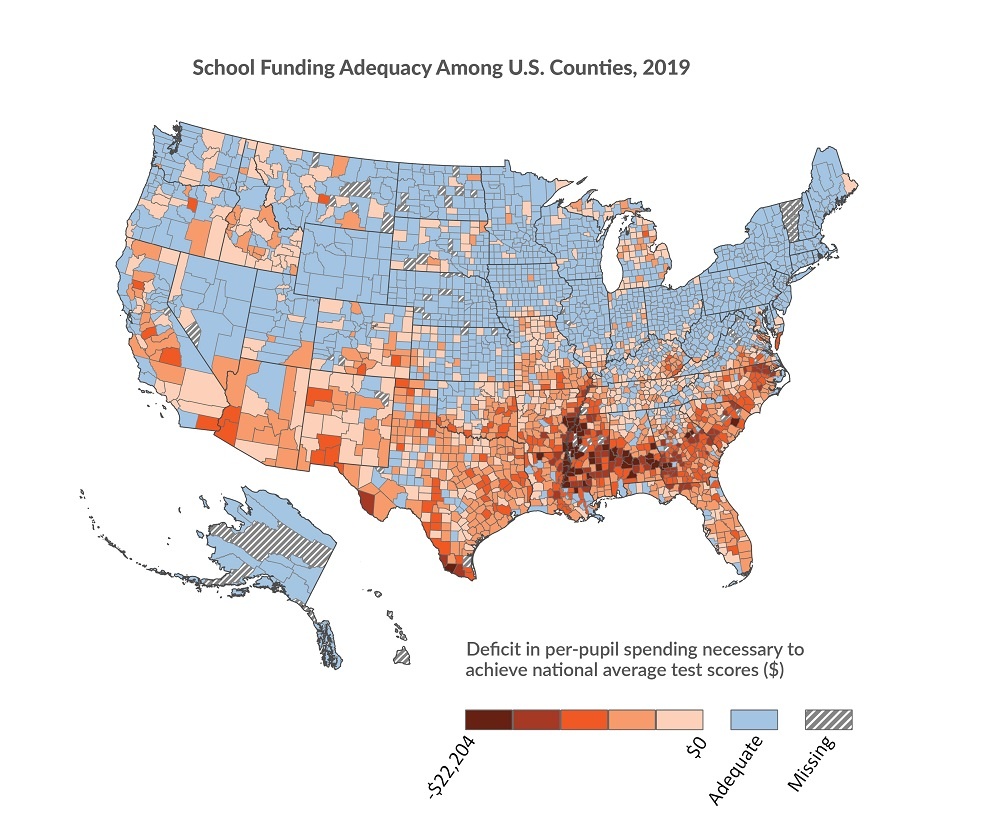

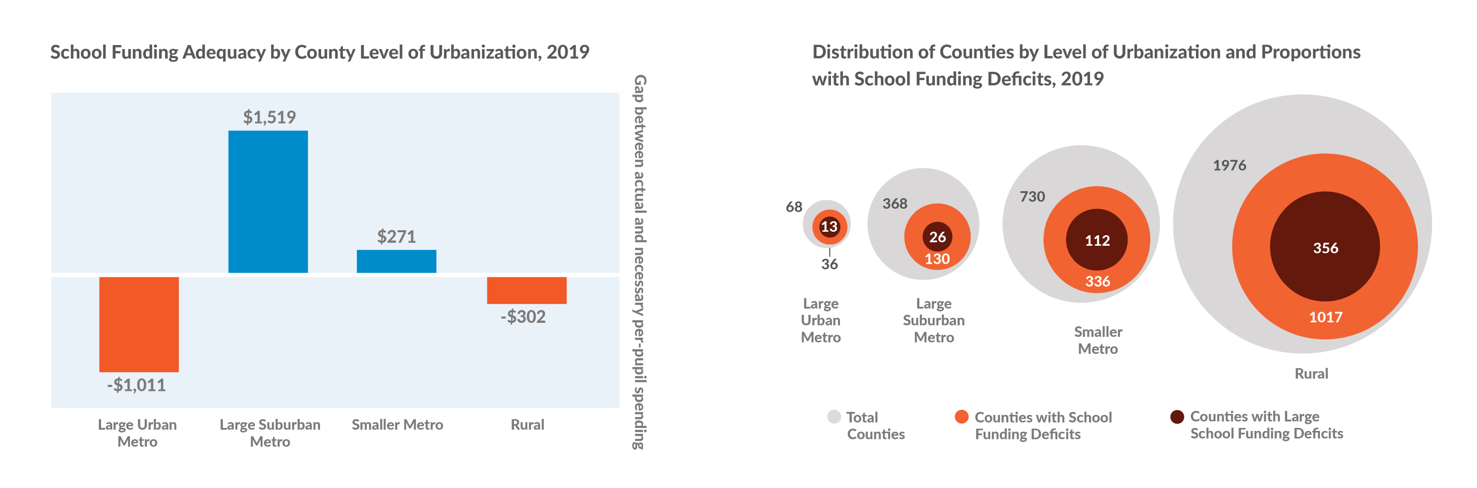

- Schools that have the resources they need to prepare their students for success are critical to creating and sustaining healthy communities. A well-funded school can help put a child on the road to academic success and a healthy, long life — an opportunity every child deserves. The reality of school funding is a stark contrast to this ideal as public schools operate with a spending deficit in half of all U.S. counties, on average needing to spend more than $3,000 more per student, annually, to support achievement of national average test scores. While schools in large urban metro counties, on average, operate under larger deficits, schools in rural counties (the majority of all U.S. counties) are overrepresented among counties affected by inadequate school funding. Funding deficits are especially high in areas such as the Southern Black Belt region with a long history of structural racism that continues to impact the flow of community resources to this day.

Advancing a Just Recovery

The COVID-19 pandemic is the worst public health crisis in more than a century and has disproportionately burdened certain communities and population groups across the U.S., particularly women, people of color, seniors, and people with low incomes. During the first full year of the pandemic, the U.S. saw the largest single-year decline in life expectancy since World War II (1.8 years, down from 78.8 years in 2019) and the largest single-year increase in the death rate on record (up 17% from 2019 to 835 deaths per 100,000 people). Provisional data for 2021 show a national death rate that remains well above the pre-pandemic level. From the beginning of 2020 through 2021, COVID-19 officially claimed more than 800,000 U.S. lives, and experts speculate the actual number could be much higher. Overall, the novel coronavirus was the third leading cause of death in 2020 and 2021 (provisional), and it was the leading cause of death in the U.S. at multiple times during those two years.

In addition to the toll the pandemic took on our physical and mental health, COVID-19 occurred at the intersection of multiple national crises — from racism to climate change — and continues to have wide-ranging negative impacts on the social and economic health of the nation. As we reported in 2020, the U.S. is still grappling with the consequences of the Great Recession more than ten years later. Following the recession and prior to COVID-19, indicators of social and economic health — such as homeownership rates and the number of children living in poverty — showed little sign of improvement. Income inequality continued to rise, and longstanding inequities in household income by race and ethnicity worsened. Available data from the beginning of the pandemic to date indicate that COVID-19 will have a similarly devastating impact, though it will likely take several more years before we truly comprehend the extent of the damage. In this year’s report, we illustrate how conditions were ripe for the pandemic to exacerbate existing health and economic disparities.

The pandemic shed light on how oppressive historic and present-day systems continue to hurt us all. As we look to recover, we have opportunities to imagine what is possible and rebuild in ways that work for everyone. We can create fair economic systems and address past harms to ensure that we are a nation where we all thrive. Advancing a just recovery requires action, including: ensuring a living wage, eliminating gender pay inequities, making childcare accessible and affordable, and funding our schools to provide quality education. These actions, and more, are needed to ensure economic security — the ability of individuals, households, and communities to meet basic needs with dignity. The pandemic highlighted many things in American society, including our ability to unite and work together for a common good. People from different backgrounds, places, and races can come together to create a better future for all.

Working Together for Fair and Living Wages

The COVID-19 pandemic brought longstanding income and wealth inequalities into full view. Advancing a just recovery requires us to address the unfair distribution of economic opportunity and resources. The struggle for economic security is shared across many communities, and the pandemic made clear we are all in this together. As we move forward, we can act on evidence-informed strategies to improve health and equity. We can ensure economic security and respect people’s dignity with strategies that:

- Reduce income inequality and recognize the value of all work by paying a living wage, supplementing income, and ensuring equal pay for equal work through policies such as paid family leave, paid sick leave, universal basic income, living wage laws, Child Tax Credit expansion, and the Earned Income Tax Credit.

- Increase employment opportunities through workforce development initiatives, including job training and leadership development programs such as transitional and subsidized jobs, high school equivalency credentials, career pathways programs, and sector-based workforce initiatives.

- Close the wealth divide that prevents many from being able to afford education, housing, and retirement and strengthen safeguards to help households navigate emergencies. Examples include: reparations for descendants of enslaved people, baby bonds, and child development accounts.

In this section, we break down the data to understand how individuals and families have struggled to earn a living wage, how women across all racial and ethnic backgrounds have continued to earn less than their male counterparts, and the implications for the economic security and health of our communities.

Living wage is the hourly wage that working individuals must earn to cover expenses for basic needs and taxes for a household with one adult and two children. Expenses for basic needs include food, childcare, health care, housing, transportation, and other necessities such as clothing, broadband service, and cell phone service. Living wage can be expressed as either dollars per hour or as a ratio to the total median wage in a county.

Ensuring Everyone’s Needs Are Met with Dignity

The cost of living in the U.S. has sharply risen over the past five decades while wages have remained relatively stagnant. Households with low incomes typically have less access to jobs that pay a living wage.* As a result, they are left with fewer options for affordable, safe housing, reliable transportation, and other necessities vital to health and well-being. Households often need to earn more than a living wage to build wealth such as saving for a college education, a down payment to purchase a home, or retirement.

Practices such as redlining and discriminatory hiring have exacerbated income inequities and access to wealth-building opportunities for communities of color. Legacies of discrimination and disinvestment have left these communities exposed to the interconnected challenges of poor health, inadequate resources, and increased exposure to environmental harms. Rural areas have also been impacted by systematic disinvestment in their economies. Within these communities, women and children have been particularly harmed by the lack of living wage jobs due to lower pay and unpaid caregiving roles. Having enough money and assets to cover basic needs and prepare for the future is essential. Economic security and good health for individuals and households are necessary for whole communities to thrive. While the pandemic brought suffering to the nation, its impact was most devastating to those whose financial well-being was already significantly threatened with wages that didn’t allow them to make ends meet.

*See Technical Note #1.

Key Findings

- On average across U.S. counties, the hourly living wage necessary to meet basic needs is $35.80 for a household with one adult and two children. Depending on location, the living wage dips to a minimum of $29.81 an hour and rises to a high of $65.45 an hour.

- Living wages are highest on the coasts and in urban counties across the U.S. where overall cost of living and housing costs are significantly higher.

- In nearly all U.S. counties, the typical wage is less than the living wage for the area. Among these counties, a more than 73% increase in wages would be necessary to meet the living wage, while some counties need as much as a 229% increase.

In Richmond, VA, the Office of Community Wealth Building launched the Richmond Resilience Initiative (RRI) with support from the Robins Foundation and the Mayors for a Guaranteed Income in December 2020. The pilot program identifies people who exceed the income requirements to receive federal social service benefits (public assistance) but still do not earn a living wage and provides participants with $500 a month over twenty-four months. The funds have no restrictions—recipients can decide what the best use of the money is for themselves and their families. At the end of the program’s third-quarter in 2021, almost 40% of RRI participants fell between stable and thriving, which means they earn enough income to pay for childcare, transportation, and housing, among other criteria. In addition, nearly half were considered stable according to the Stability Measure Tool, an assessment used by Richmond’s Office of Community Wealth Building to measure if participants are in crisis, at risk, safe, stable, or thriving. Participants reported a wide range of goals they addressed with the additional income, including credit repair and saving for future homeownership and unforeseen expenses.

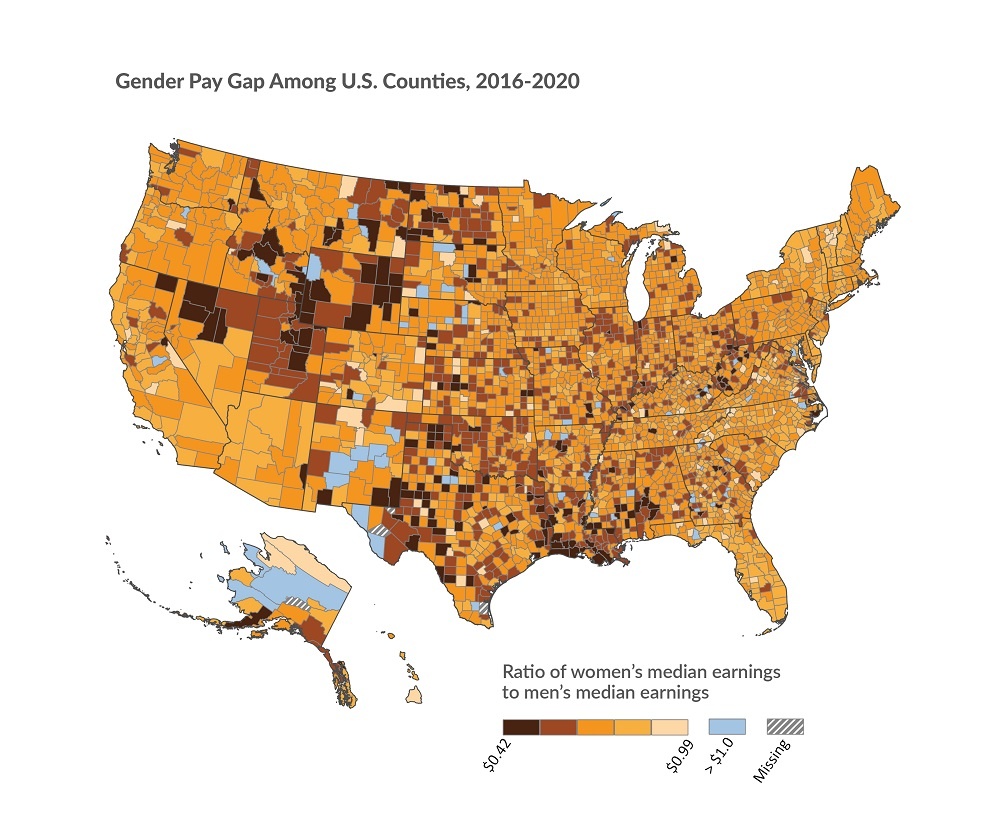

Gender Pay Gap is the ratio of women’s median earnings to men’s median earnings for all full-time, year-round workers, presented as “cents on the dollar.”

Unfair Obstacles Persist for Equal Pay

Stable, living-wage jobs and fair pay are essential for healthy communities. Yet, women across all races and ethnicities earn less than men do, on average, for the same roles in nearly every occupation. Women earn little more than 80 cents for every dollar men earn, nearly 60 years after the Equal Pay Act was passed to ban wage discrimination based on gender.

Racial and gender employment discrimination remains a constant in the U.S. and influences all stages of employment — from hiring, to performance reviews,

to layoffs. Though women’s educational attainment surpasses that of men, they are often segregated into low-wage jobs and are still paid less than men for the same work. The gap exists across nearly all occupations, even in female-dominated sectors such as service, education, and health care, and widens as women attain higher positions.

The gender pay gap impacts the health of women, families, and communities. Overall, when women have opportunities, such as a fair chance for education, employment, and earnings, they are more likely to live longer and healthier lives, and their children fare better. The gender pay gap also undermines the financial stability and economic prospects for families and communities.

Women’s participation in the labor force dropped to a 30-year low during the pandemic, the result of layoffs and added caregiver responsibilities. Those who remained, particularly those with lower incomes, were likely to hold jobs that defined them as “essential workers” in health care, social work, government, and community-based services. Still, these women earned much less than their male counterparts.

For the nation’s women who work outside the home, particularly for women of color, decades of economic insecurity and pay inequity have been made even worse by the pandemic. The pandemic exposed the labor force barriers that prevent full participation of women and caregivers. The lack of work-family supports such as paid sick leave or paid family leave, coupled with the high cost of childcare, places an additional burden on women with low incomes and women of color, who are the least likely to have employer-provided benefits.

Building economic security is imperative for health, yet pay inequity and lost earnings due to the wage gap have dire consequences for women and their families resulting in fewer opportunities to make ends meet, let alone save for emergencies or retirement. The pay gap sheds light on the systemic undervaluing of women’s contributions to the workforce and economy. Equal pay can be part of a recovery that begins to reverse these trends and center fairness and opportunity for all.

Key Findings

- Women earn less than men in most counties, on average. The size of the pay gap varies across the U.S., with concentrations of wide gaps in the South and the Western Plains.

- Median earnings and the gender pay gap vary significantly by race and level of urbanization.* Hispanic, American Indian & Alaska Native, and Black women, along with women living in rural areas, earn the least across categories.

- When looking at the pay gap between men and women across racial groups and level of urbanization, the largest gaps exist between men and women living in rural or suburban areas.

- Women of all races and ethnicities must work several more days if not months more to earn the $61,807 average annual salary of a white man. Hispanic women must work the longest — an additional 299 days, or nearly 10 months.

*See Technical Note #2.

For the past 50 years, National Women’s Law Center’s (NWLC) fight for gender justice — in the courts, in public policy, and in our society — has centered on issues impacting the lives of women and girls, especially women of color, LGBTQ people, women and families with low incomes. Two areas of focus for NWLC include: ensuring a safe place of work for women, and access to affordable, high-quality childcare. Through advocacy and education, NWLC elevates attention on wage gaps across gender and race, and advocates to address the systemic problems that threaten economic security for many in our country. NWLC supports the creation of a childcare system that works for everyone — families, early educators, and children — and that values caregiving work as essential to society as a whole. Their research was fundamental to the historic investments made to stabilize the childcare system in the American Rescue Plan and continues to help drive a conversation about long-term investments in building a childcare and early learning system that works for all. To that end, NWLC launched a narrative campaign “We Are the Backbone” to lift up the childcare workforce and ensure that Black and Brown women are centered in childcare policy decisions. Through this work, NWLC makes certain those most impacted are shaping the solutions for a more equitable COVID-19 recovery.

Creating Community Conditions for Families to Thrive

In addition to providing a living wage and closing the pay gap, quality education systems, and affordable and accessible childcare are community resources that support and promote economic security and collective well-being. Advancing a just recovery requires more robust resources for communities. We can reshape systems and redirect funding where it is most needed to:

- Increase access to affordable childcare, which creates opportunities for caregivers to participate in the workforce, keeps children safe, and provides early childhood education. Examples include publicly funded pre-kindergarten programs, child care subsidies, preschool education programs, and Early Head Start.

- Improve community conditions and increase access to financial resources to preserve affordable housing. Local property taxes increase with home values, allowing for more school funding and other community resources. This can be achieved through Community Development Financial Institutions, Community Development Block Grants, inclusionary zoning and housing policies, housing reparations, and Tax Increment Financing (TIF) for affordable housing.

- Build social connectedness, cultivate community power, and promote civic engagement by addressing barriers to participation in policymaking, resource allocation, information sharing, and collaboration in neighborhoods, schools, and workplaces. Examples include community schools, school-based health centers, youth leadership programs, and community health workers.

The COVID-19 pandemic hit families hard as communities contended with the impact on schools and childcare providers. Families and educators faced the unprecedented task of providing quality care and education while keeping children safe and healthy. In this section, we look back at the heavy burden that communities, already facing economic hardship, including higher childcare costs and under-funded schools, withstood.

Balancing Work and Home Life for Families with Children

Access to affordable, high-quality childcare allows parents and caregivers to participate in the workforce, provides an entry into childhood education, and supports a lifetime of academic achievement. An affordable childcare system requires adequate public funding and enough licensed providers, especially in communities with more households with low incomes.

Childcare Cost Burden is the childcare cost for a household with two children as a percentage of median household income.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ benchmark suggests childcare is not affordable if it exceeds 7% of a household’s income.* High childcare cost burden can force families to make difficult choices between paying for basic needs such as housing, food, transportation, and medical care.

Amid mass school and childcare center closures, many parents and caregivers who lacked affordable childcare left the workforce during the pandemic. This was especially true for women, who were more likely to hold “essential” jobs and to be paid less than their male counterparts. The economic security and health of our communities relies on safe and enriching places for children to learn and develop, allowing parents and caregivers to participate in the workforce.

*See Technical Note #3.

Key Findings

- The average U.S. county has six childcare centers per 1,000 children under age 5.* This is half of the number of centers in counties with the most access, at 12 or more childcare centers per 1,000 (90th percentile).

- There are no counties where childcare cost for two children is at or below the 7% benchmark. On average across counties in the U.S., a family with two children spends 25% of its household income on childcare, more than three times the 7% benchmark. Childcare cost burden is highest in large urban metro (27%) and rural counties (25%).

- For someone earning the federal $7.25-an-hour minimum wage, the average cost of childcare across U.S. counties for two children is more than 90% of their annual income. The average childcare provider likely cannot afford their own services, which would consume more than half their average $25,460 annual income if they had two children.

- With a combined annual income of more than $100,000, the average married couple with children pays nearly double the 7% benchmark for childcare. A single woman with children pays 45% of her annual $30,681 salary toward childcare. A single man with children pays 29% of his annual $47,375 salary toward childcare.

*See Technical Note #4.

Understanding it takes a village to raise a child and ensure the health and development of young children, Gonzales, CA, joined forces in 2018 with the United Way of Monterey County, First 5 Monterey County, and Community Action Partnership of San Luis Obispo to launch the Family, Friends & Neighbor Network. With only about a third of children countywide having access to licensed care, the program supports those caring for children in their home by helping them better understand how they can foster a child’s healthy development through various activities. Twice a month for two hours, children from 10 months to 4 years old participate in play groups where they learn skills such as active listening and empathy. Network leaders plan each session and are supported with professional development to help toward future licensure. To further improve the quality of home-based care, the network helps caregivers learn valuable skills on everything from social-emotional development to early childhood safety.

Schools Provide Community Infrastructure

All children deserve access to quality education. However, the inequitable way public school systems receive funding reflects a history of structural racism. After the 1964 Civil Rights Act prohibited discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, racial and ethnic segregation in public schools declined, but only for a couple of decades. The legacy of inequity continues today in the form of unequal access to well-funded, quality schools. White families, regardless of income, tend to live in communities with well-funded school districts. They also have greater access to private and charter schools than families of color have.

School funding adequacy is a measure of per-pupil spending in public school districts compared to the estimated spending required to achieve national average test scores. The estimate accounts for cost differences between districts, labor costs, district size, and the share of high-need students, among other factors. Of note, test scores are not the only important educational outcome. Students’ access to qualified teachers and programs can add to a more complete understanding of broader educational goals.

Some families have enough resources to choose homeschooling. Others have opportunities to enroll their children in private schools. These practices can lead to economic segregation, impacting the flow of resources to public school districts, which depend on student enrollment. The pandemic further disrupted the allocation of school resources. Many schools laid off teachers and reduced school programs, food services, and transportation. Some shifted budgets to hire more nurses and buy virtual learning equipment. Although the pandemic upended the lives of all students, students of color and students in rural areas were more likely to attend schools with inadequate funding prior to the pandemic.

Children living in rural and urban counties experience varying educational opportunities, largely based on underlying social and economic circumstances and historical factors. For example, the mass exodus of white families from urban neighborhoods to the suburbs in the 1940s shifted people, opportunities, and investment. In rural counties, a history of deindustrialization and a shift toward corporate farming, for example, has similarly extracted resources out of these communities. Schools in areas with high poverty struggle to match the per-pupil spending of wealthier communities — a consequence of depressed home values, which generate less revenue through property tax collections. Through these mechanisms, the experience of poverty and its related barriers to health can combine with the disadvantage of learning in an under-resourced school, ultimately hindering children, especially in urban and rural areas, from achieving their full potential.

Key Findings

- There are major geographic differences in school funding adequacy* rooted in histories of racial discrimination, violence, and exclusion. Many counties in the Western and Southern U.S. operate with funding deficits. School districts in these counties, on average, spend less than what is estimated to be necessary to achieve national average test scores. Counties with higher proportions of Black, Hispanic, and American Indian & Alaska Native populations experience funding deficits notably greater than most U.S. counties. Funding deficits are especially high in areas such as the Southern Black Belt region.*

- Half of all counties in the U.S. operate with a public school funding deficit, on average needing to spend more than $3,000 more per student, annually.

- Students attending public schools in large suburban and smaller metro counties benefit, on average, from adequate school funding, while public school students in large urban metro and rural counties attend schools that operate with a deficit (more than -$1,000 per student, annually, in large urban counties).

- Rural counties, which represent the majority of all U.S. counties, are disproportionately represented among counties with school funding deficits, particularly those with large deficits* (70% of counties with deficits of more than -$4,500 per student, annually, are rural).

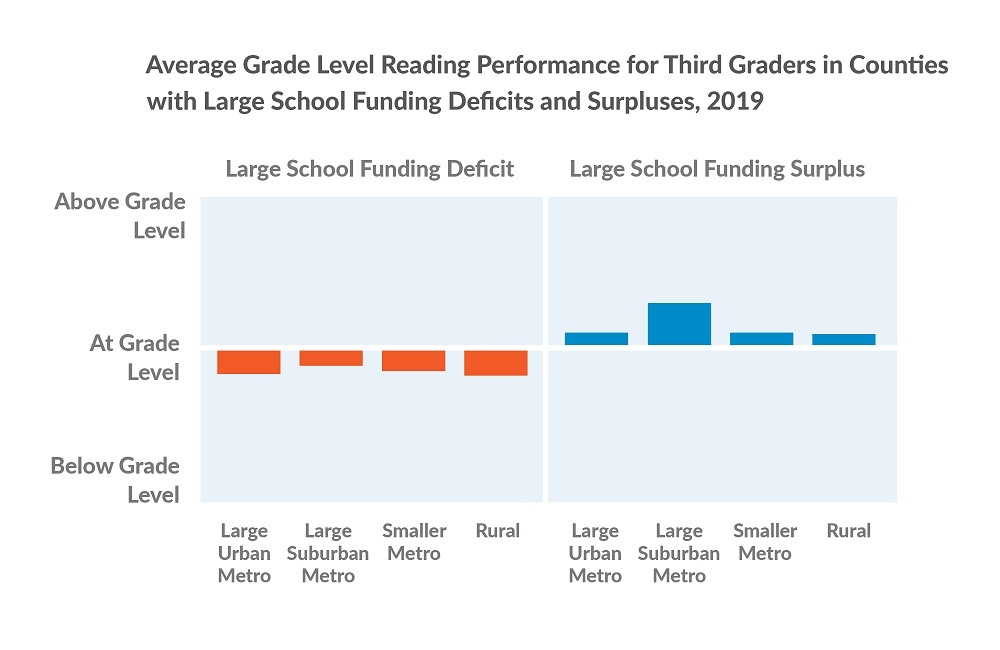

- Across all community types, large school funding deficits (more than -$4,500 per student, annually) correlate with students performing below their grade level for reading (and math, not shown). Students performed above their grade level, on average, in schools with large funding surpluses (more than $3,782 per student, annually).

*See Glossary of Terms and Technical Notes #5 and #6.

Rocky Mount, NC, anchors its health strategy in the expertise and voices of the residents who call it home. Determined to change longstanding power dynamics due to the historic division that disadvantaged one side of town in favor of the other, residents are encouraged to take leadership positions on various city-organized boards and commissions. The Community Academy, which brings together leaders from 14 neighborhood associations, partnered with Legal Aid of North Carolina-Rocky Mount to promote equal housing opportunity through the city’s Fair Housing assessment process. Transforming Rocky Mount, a collective of local organizations, is also working to ensure historically excluded populations have a voice in the creation, provision, and assessment of city policies and programs, generating new potential for community-led decisions. Economic and workforce development opportunities are being cultivated through a mix of efforts, including the Community Wealth Building Initiative, which is designed to strengthen neighborhoods through local ownership and control of business, jobs, and housing.

A Call to Action

The pandemic highlighted the interdependence of the public health, community and economic development and education sectors. Public infrastructure and strong social systems nurture our collective well-being and show us what is possible when we work together. This report is a call to action to strengthen relationships across sectors to advance economic security and health for everyone.

We encourage you to consider the national findings from this report, dig into local data to understand the health of specific communities, and work together to implement strategies that promote health and equity. By recognizing how historic and current policies and systems create disadvantage, we can allocate resources where they are most needed so that economic inclusion, good health, and prosperity are shared by all.

About County Health Rankings & Roadmaps

County Health Rankings & Roadmaps (CHR&R), a program of the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, is working to improve health outcomes for all and close health gaps between those with the most and least opportunities for good health. This work is rooted in a deep belief in health equity, the idea that everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible, regardless of race, ethnicity, gender, income, location, or any other factor.

As illustrated in the model at the right, a wide range of factors influence how long and how well we live, from education and income, to what we eat and how we move, to the quality of our housing and the safety of our neighborhoods. For some people, the essential elements for a healthy life are readily available; for others, the opportunities for healthy choices are significantly limited due to power imbalances in decision-making and resource allocation.

These differences in opportunity do not come about on their own. We have the collective capacity to implement policies and programs that positively influence how resources are allocated, how services are provided, how groups are valued, and, ultimately, our health. CHR&R seeks to foster social solidarity and help build community power for health equity.

Supporting materials, such as detailed data tables, are available here.

Glossary of Terms and Technical Notes

Glossary of Terms

Health Equity: Assurance of the conditions for optimal health for all people. Achieving health equity requires valuing all individuals and populations equally, recognizing and rectifying historical injustice, and providing resources according to need.

Health Inequity: Differences in health outcomes that are systematic, avoidable, unnecessary, unfair, and unjust.

Health Disparity: The numerical or statistical differences in health outcomes, such as mortality rate differences. Reducing and ultimately eliminating disparities in health and its determinants of health is how we measure progress toward health equity.

Social Solidarity: Emphasizes the interdependence between individuals in a society, which allows individuals to feel that they can enhance the lives of others. It is a core principle of collective action and is founded on shared values and beliefs among different groups in society.

Structural Racism: A system in which public policies, institutional practices, cultural representations, and other norms work in various, often reinforcing ways to perpetuate racial group inequity.

Oppression: The systematic subjugation of one social group by a more powerful social group for the social, economic, and political benefit of the more powerful social group.

Community Power: The ability of communities most impacted by structural inequity to develop, sustain, and grow an organized base of people who act together through democratic structures to set agendas, shift public discourse, influence who makes decisions, and cultivate ongoing relationships of mutual accountability with decision makers that change systems and advance health equity.

Black Belt region: A term used to define a geographic region from east-central Mississippi to Virginia Tidewater and has origins in reference to the dark color of rich and productive soil located there. These counties are where the cotton-slave-plantation-complex developed and agriculture was most profitable for enslavers during the years preceding the Civil War. In present day, these counties have a larger proportion of the population that is Black compared to most U.S. counties.

Redlining: The Federal Housing Administration's policies from the 1930s that entrenched racial residential segregation. Redlining denied people of color access to government-insured mortgages and labeled homes in neighborhoods where people of color lived as uninsurable, thereby guaranteeing that property values in those neighborhoods would be less than those in white neighborhoods. Sociologist James McKnight is credited with the term ‘redlining’ referring to red lines lenders would draw on a map around neighborhoods they would not invest in based on demographics alone.

Technical Notes

- Living Wage values are reported in 2021 dollars. We characterize the basic needs budget and living wage according to a one-adult, two-children household to better reflect how societal structures such as the gender pay gap and minimum wage laws close opportunities for single adults, especially women, to support their children.

- We define levels of urbanization as: Rural (non-metropolitan counties with less than 50,000 people); Smaller Metro (counties within a metropolitan statistical area, or MSA, with between 50,000 and one million people); Large Suburban Metro (non-central fringe counties within an MSA with more than one million people); and Large Urban Metro (central urban core counties within an MSA with more than one million people).

- The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services published a 2016 update to rules and regulations for the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) program, which helps cover childcare costs for children from households with low incomes. The updated rules established a federal benchmark for an enrolled family’s childcare co-payments to be considered unaffordable if costs exceed 7% of household income. The benchmark has since been applied outside of the context of the CCDF program to indicate that families with low and middle incomes should not spend more than 7% of their income on childcare for it to be considered affordable.

- Childcare centers is the number of center-based child daycare locations (including those located at school and religious institutes, but not group, home, or family-based childcare) per 1,000 population under 5 years old.

- School funding adequacy is calculated for each public school district. The county value is the cross-district average of the funding below or above the estimate for the required amount of per-pupil spending to achieve national average test scores. We characterize these values as “funding deficits” and “funding surpluses,” respectively. However, we recognize that schools may overperform or underperform their funding levels, and the term surplus should not be interpreted as excess or wasteful. The formulas allocating spending on education vary by state and by school districts within states. Determining the formulas and providing the majority of the funding is within the purview of state and local governments.

- Counties considered to have large surpluses or deficits in school funding adequacy were those in the highest tertile (66th percentile) of values. Large deficits are considered those ≥-$4,500 per student, annually. Large surpluses are considered those ≥$3,782 per student, annually.

How did we select the evidence-informed solutions?

Evidence-informed solutions are supported by robust studies or reflect recommendations made by experts. To learn more about our evidence analysis methods, visit What Works for Health.

How do we define racial and ethnic groups?

We recognize that “race” and “ethnicity” are social categories. Society may identify individuals based on their physical appearance or perceived cultural ancestry, as a way of characterizing individuals' value. These categories are not based on biology or genetics. A strong and growing body of empirical research provides support for the fact that genetic factors are not responsible for racial differences in health factors and very rarely for health outcomes.

We are bound by data collection and categorization of race and ethnicity according to the U.S. Census Bureau definitions, in adherence with the 1997 Office of Management and Budget standards.

Our analyses also do not capture those reporting more than one race, of “some other race,” or who do not report their race. This categorization can mask variation within racial and ethnic groups and can hide historical context that underlies health differences.

How do we define gender?

We recognize that while the terms “gender” and “sex” are often used interchangeably, they do not represent the same concept. Sex is generally assigned at birth based on the observed anatomy, while gender is a social construct wherein certain tendencies or behaviors are assigned by society to labels of masculine or feminine. We know that neither gender nor sex are binary constructs and that people living intersectional identities (e.g., transgender women) experience compounding power differentials, which are not captured in a binary delineation between men and women.

Using “Gender Pay Gap” to describe the ratio of women’s median earnings to men’s median earnings follows common naming conventions and maintains consistency with other sources. However, it can contribute to the conflation and oversimplification of these concepts of gender and sex. Data for this measure come from the U.S. Census Bureau, which words the question around sex to intentionally capture an individual’s assigned sex and not their gender.

Suggested Reading

Find relevant research and evidence for key topics and their connection to health in the 2022 National Findings Report.

Land Acknowledgement

The University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute occupies Ho-Chunk land, a place their nation has called Teejop (Day-JOPE) since time immemorial. In 1832, the Ho-Chunk were forced to surrender this territory. Decades of genocide followed when both the federal and state government repeatedly, but unsuccessfully, sought to forcibly remove the Ho-Chunk people from Wisconsin. This history of colonization informs our shared future of building partnerships that prioritize respect and meaningful engagement. The staff of the institute respects the inherent sovereignty of the Ho-Chunk Nation, along with the eleven other First Nations of Wisconsin. We operationalize our values by considering the many legacies of violence, erasure, displacement, migration, and settlement. We carry these truths as we work to make positive change.

Credits

Recommended citation

University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. County Health Rankings National Findings 2022.

This work is made possible with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Thank you to National Women’s Law Center and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Culture of Health Prize-winning communities of Rocky Mount, NC (2020-2021); Gonzales, CA (2019); and Richmond, VA (2017) for sharing their stories and work featured in this report.

Lead Authors

Keith Gennuso, PhD

Michael Stevenson, MPH

Christine Muganda, PhD

Sheri Johnson, PhD

Marjory Givens, PhD, MSPH

This publication would not have been possible without the following contributors:

Research Assistance

Elizabeth Blomberg, PhD

Suryadewi Nugraheni, MD, MA, PhD

Nicholas Schmuhl, PhD

Jess Hoffelder, MPH

Ganhua Lu, PhD

Jennifer Robinson

Matt Rodock, MPH

Anne Roubal, PhD

Molly Burdine

Hannah Olson-Williams

Eunice Park, MIS

Ben Case, MPH

Kiersten Frobom, MPA, MPH

Lael Grigg, MPA

Bomi Kim Hirsch, PhD

Naiya Patel, MPA, MPH

Jessica Rubenstein, MPA, MPH

Jessica Solcz, MPH

Gillian Giglierano

Amanda Gatewood, PhD

Molly Murphy, PhD

Everett Trechter, MPP

Molly Wirz, MS

Data collaborator

Amy Glasmeier PhD, MA

Outreach Assistance

Beth Silver, MCM

Ericka Burroughs-Girardi, MA, MPH

Tommy Jaime, MA

Colleen Wick

Lindsay Garber, MPA

Carrie Carroll, MPA

Angela Acker, MPH

Olivia Little, PhD

Jonathan Heller, PhD

Wajiha Akhtar, PhD, MPH

Scientific Advisory Group

Renée Branch Canady, PhD, MPA

David Chae, ScD, MA

Jim Chase, MHA

Tracy A. Corley, PhD

Katherine Cramer, PhD

Marah Curtis, PhD

Tom Eckstein, MBA

Kurt Greenlund, PhD

Carolyn Miller, MA, MS

Ryan Petteway, DrPh, MPH

Pat Remington, MD, MPH

Steven Teutsch, MD, MPH

Trissa Torres, MD, MSPH, FACPM

Operations

Plumer Lovelace III

Tricia Ballweg

James Lloyd, MS

Erin Schulten, MPH, MBA

Cathy Vos

Communications and Website Support

Burness

Forum One