About the Structural Determinants of Health Curated Strategy List

This list of evidence-informed strategies addresses the structural determinants of health. It focuses on building power and changing laws, policies, budgets and worldviews to improve the conditions that shape health.

What are the structural determinants of health?

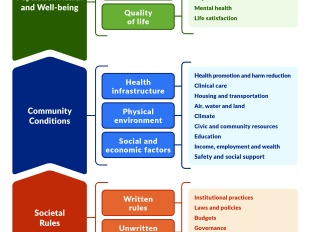

Many factors contribute to health. Safe housing, jobs that pay a living wage and well-resourced schools are among the conditions, often called the social determinants of health, that make up a healthy community. How these conditions are created, distributed and maintained determines everyone’s opportunity to thrive. Written and unwritten societal rules – and how they are applied – shape conditions for healthy communities. Rules may be written in the form of policies and laws, or unwritten, in the form of worldviews and norms. Together, power and rules are the structural determinants of health.1

People with power create, reinforce and modify these rules for their benefit. People and groups who hold power influence society’s rules and determine whether they are applied equitably. When power is concentrated in the hands of a few, it advantages their shared interests and often disadvantages interests aligned with good health for all. How well we include everyone in setting agendas, making decisions and sharing resources determines whether we can promote and preserve health for all. Everyone should have a say in creating society’s rules and in determining how they are applied.

How is power related to health?

Power is the ability to achieve a purpose and to effect change. People can build power in communities when they organize and act together to set agendas, shift public discourse, influence who makes decisions and cultivate relationships with decision makers.

The health and well-being of people and places is determined by the ability — particularly for those most impacted by inequities — to make change that supports social, economic or environmental conditions needed to thrive. People can use their power to challenge laws and policies, institutional practices, worldviews, culture and norms. In the ongoing negotiation of social, political and economic resources, those with power can either maintain society’s rules or make changes that can improve health and advance equity.2

For example, after women organized and won the right to vote in 1920, infant mortality rates dropped dramatically when lawmakers passed a law that set up maternal and child health units in every state health department, expanded birth and death data collection and supported home-visiting initiatives.3 The Civil Rights Act, which included hospital desegregation, is also associated with health improvement. From 1965 through 1971, infant mortality rates dropped and the gap between Black and white infant mortality narrowed.4 This followed the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, which shifted electoral power and ushered in a new era of government responsiveness to Black and other marginalized populations’ voter participation.5

People have also used power to reinforce rules that maintain patterns of social, economic and health inequity. For example, the tobacco industry has wielded corporate power to promote tobacco use and undermine public health efforts. Tobacco industry leaders have done so by lobbying against regulations that limit advertising, advocating for legislation that minimizes restrictions on tobacco sales, and marketing to marginalized communities. Through financial contributions to political campaigns and public health organizations, tobacco companies have also influenced governance and public perception, creating a façade of corporate responsibility while continuing practices detrimental to health.6

How do societal rules impact health?

Societal rules are both written and unwritten and shape community conditions. Written rules may be formalized and documented in laws, policies, regulations and budgets. Unwritten rules are made up of worldviews, culture and norms. These can include customs or expectations that guide acceptable thought and behavior. Institutional practices and systems of governance —such as an organization’s approach to salary parity —may be written or unwritten.

Societal rules shape the community conditions that impact how well and how long we live. Societal rules can address population health issues, such as through laws that require children to be vaccinated before attending public school. More often, societal rules shape the conditions that influence health and equity based on place, race and other societally constructed differences. For example, the Earned Income Tax Credit is a policy that offers a refundable income tax credit to low- and moderate-income individuals and families. There is strong evidence that the Earned Income Tax Credit increases employment and earnings for mothers and thereby improves maternal and child health.

Which strategies will improve the structural determinants of health?

Improving health through the structural determinants involves individual and collective actions in addition to local, state and federal solutions. Strategies may be a law, budget or policy, institutional or governance practice, or related to a worldview that can be changed to potentially redistribute power. The effectiveness of these strategies depends on how people gain agency and influence in decisions that affect their lives.

Related resources

References

- Heller, J. C., Givens, M. L., Johnson, S. P., & Kindig, D. A. (2024). Keeping it political and powerful: Defining the structural determinants of health. Milbank Quarterly, 102(2), 351-366. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12695

- University of Southern California Dornsife Equity Research Institute. (2020). A primer on community power, place, and structural change. https://dornsife.usc.edu/eri/wp-content/uploads/sites/41/2023/01/Primer_on_Structural_Change_web_lead_local.pdf

- Miller, M. (2008). Women's suffrage, political responsiveness, and child survival in American history. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(3), 1287-1327. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2008.123.3.1287

- Anderson, D. M., Charles, K. K., & Rees, C. I. (2023). Imposing policy on reluctant actors: The hospital desegregation campaign and Black postneonatal mortality in the Deep South [Working paper]. National Bureau for Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w27970

- Crayton, K. (2023, July 17). The Voting Rights Act explained. Brennan Center for Justice. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/voting-rights-act-explained

- Rotman, B., Ballweg, G., & Gray, N. (2022). Exposing current tobacco industry lobbying, contributions, meals, and gifts. Tobacco Induced Diseases, 20(January), 3. https://doi.org/10.18332/tid/144765