What Works? Social and Economic Opportunities to Improve Health for All

Creating Healthy and Equitable Communities

How much stronger could our communities be if all of our children attended high quality schools, if everyone earned enough money to afford essentials, and if we all felt connected to our communities, regardless of where we live, the circumstances we are born into, or the color of our skin? When we work together to improve education, employment, income, and family and social supports—the social and economic factors that influence our communities—we can improve the health of all who live, learn, work, and play there.

Creating healthier communities where everyone can thrive and have a voice in the process for creating solutions requires bringing people together to:

- Look at the many factors that influence health,

- Select strategies that can improve everyone’s health, and

- Make changes that will have a lasting positive impact.

There is no single strategy that can ensure everyone in a community can be healthier. The County Health Rankings model helps us understand the many factors that influence health, and should be considered in an approach to improving health in a community. Social and economic factors like education and income are not commonly considered when it comes to health, yet strategies to improve these factors can have an even greater impact on health over time than those traditionally associated with health improvement, such as strategies to change behaviors.

This report outlines key steps toward building healthier and more equitable communities and features specific policies and programs that can improve social and economic opportunities and health for all. Policies and programs that are likely to reduce unfair differences in health outcomes are emphasized.

How Can Jobs, Education, and Social Supports Improve Health and Equity?

Health is about more than what happens at the doctor’s office—it is influenced by a range of factors. The places where we live, learn, work, and play, the opportunities we have, and the choices we make all matter to our physical, mental, and social well-being. Social and economic opportunities, such as good schools, stable jobs, and strong social networks are foundational to achieving long and healthy lives. These opportunities affect our ability to make healthy choices, afford medical care and housing, and manage stress.

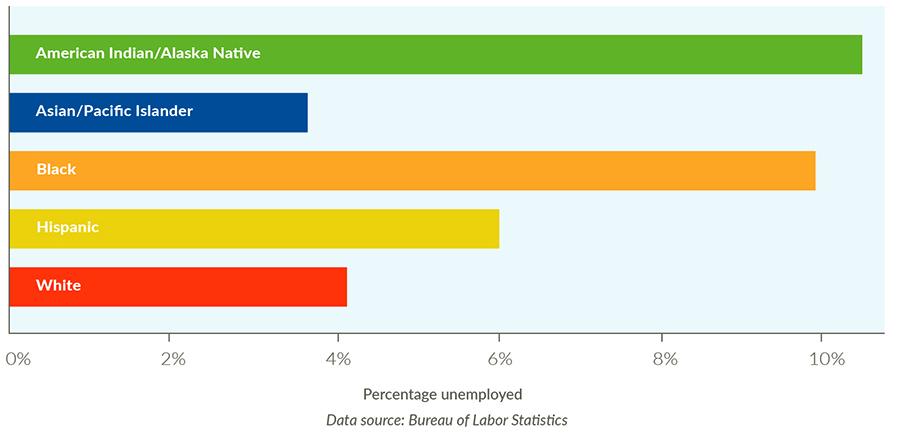

Not everyone has the means and opportunity to be their healthiest. Across the nation, there are meaningful differences in social and economic opportunities for residents in communities that have been cut off from investments or have experienced discrimination. These gaps in opportunities disproportionately affect people of color—especially children and youth.

Policies and practices put in place have marginalized population groups and communities, such as people of color, keeping them from the resources and supports necessary to thrive. Limited access to opportunities creates disparities in health, impacting how well and how long we live. These differences in opportunity can be narrowed, if not eliminated, if we take ongoing, meaningful steps to create more equitable communities.

Here’s a closer look at how each of the social and economic factors influence health.

Finding Strategies that Work

This report can help you get started on the path to creating healthier, more equitable communities by selecting strategies to improve social and economic factors and remove barriers to opportunity. A good first step is to explore strategies that have worked in other communities or are recommended by experts. With evidence ratings, literature summaries, and implementation resources for more than 400 strategies, What Works for Health (WWFH) is a great place to start.

WWFH offers in-depth information for a variety of policies and programs that can improve the many factors that influence health, including social and economic opportunities, health behaviors, clinical care, and the physical environment. For each policy and program, you will find:

- Beneficial outcomes (i.e., the benefits the strategy has been shown to achieve as well as other outcomes it may affect)

- Key points from relevant literature (e.g., populations affected, key components of successful implementation, cost-related information)

- Implementation examples and resources, toolkits, and other information to help you get started

- An indication of the strategy’s likely impact on the gaps or disparities in outcomes among groups of people (e.g., differences among racial, ethnic, or socio-economic groups)

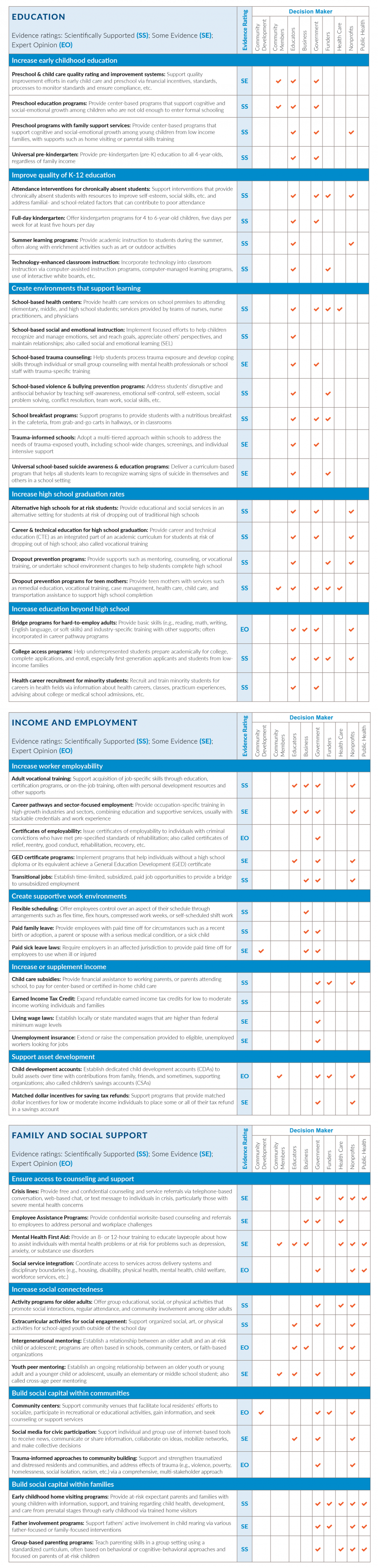

This report outlines some of the policies and programs you will find in WWFH to support local initiatives to:

- Improve educational outcomes

- Increase income and employment

- Build family and social support

These examples emphasize policies and programs that are likely to reduce disparities in health outcomes, and those with strong evidence of effectiveness. To see the full list of strategies in WWFH, go to countyhealthrankings.org/whatworks.

Evidence Rating

WWFH includes six evidence of effectiveness ratings. Each strategy is rated based on the quantity, quality, and findings of relevant research.

Ratings include:

- Scientifically Supported (SS): Strategies with this rating are most likely to make a difference. These strategies have been tested in multiple robust studies with consistently positive results.

- Some Evidence (SE): Strategies with this rating are likely to work, but further research is needed to confirm effects. These strategies have been tested more than once and results trend positive overall.

- Expert Opinion (EO): Strategies with this rating are recommended by credible, impartial experts but have limited research documenting effects; further research, often with stronger designs, is needed to confirm effects.

- Insufficient Evidence (IE): Strategies with this rating have limited research documenting effects. These strategies need further research, often with stronger designs, to confirm effects.

- Mixed Evidence (Mixed): Strategies with this rating have been tested more than once and results are inconsistent; further research is needed to confirm effects.

- Evidence of Ineffectiveness (EI): Strategies with this rating are not good investments. These strategies have been tested in multiple studies with consistently negative or harmful results.

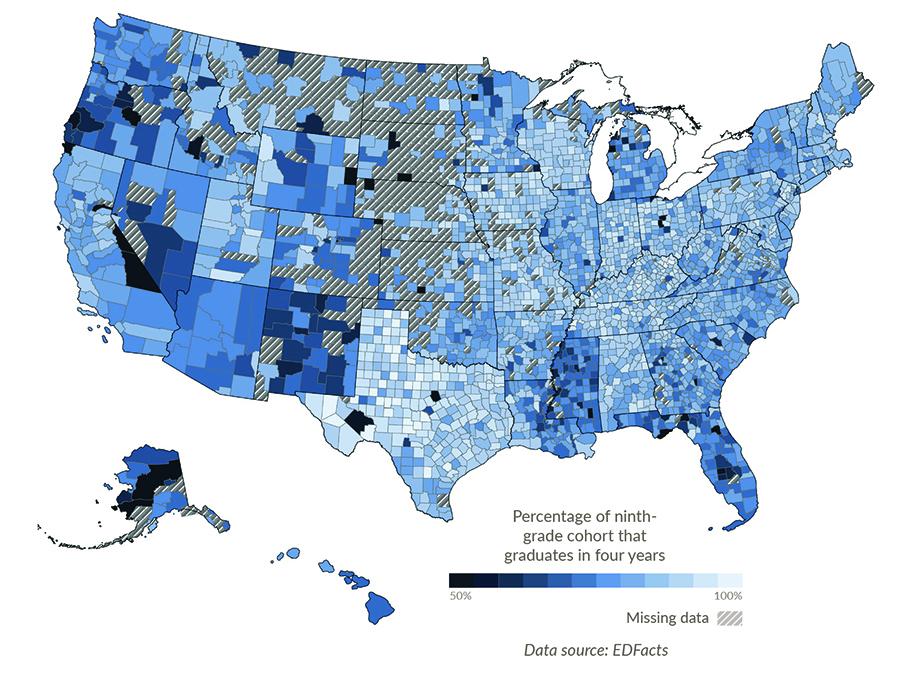

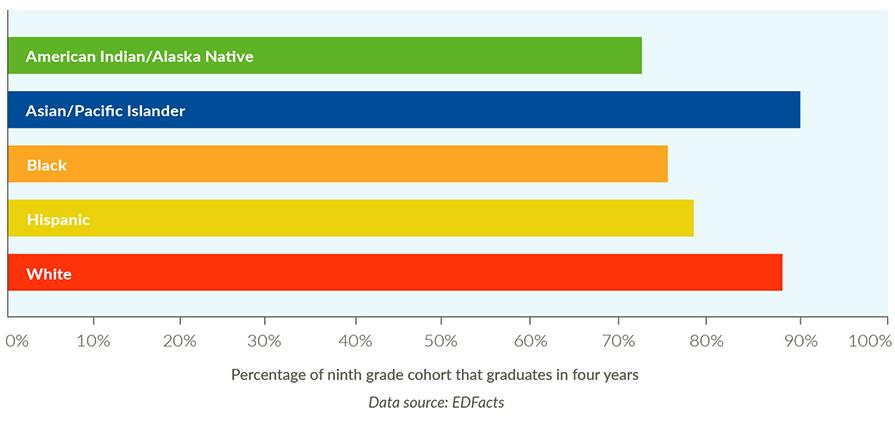

A Look at Education

Individuals with more education live longer, healthier lives than those with less education, and their children are more likely to thrive. This is true even when factors like income are taken into account. Across the U.S., there are large gaps in educational attainment between people who live in the least healthy counties and those in the healthiest counties. Often, for American Indian/Alaskan Native, Black, and Hispanic people, barriers to educational attainment create gaps within communities that are similar, if not greater. Educational institutions, governments, funders and community members can work together to set all children and young adults on a path towards academic and financial success.

What’s Working to Improve Educational Outcomes?

Examples of approaches and strategies with strong evidence of effectiveness that communities can implement to improve educational outcomes include:

Increase early childhood education, for example:

- Preschool education programs provide center-based support and learning for young children

- Universal pre-kindergarten provides early education for all 4-year-olds

Improve quality of K-12 education, for example:

- Attendance interventions for chronically absent students include resources and support to address individual, familial, and school-related factors that contribute to poor attendance

- Full-day kindergarten offers early education for 4- to 6-year-olds, every weekday for at least five hours

- Summer learning programs provide continuous learning throughout the year

Increase high school graduation rates, for example:

- Alternative high schools for at-risk students provide an alternative setting for education

- Dropout prevention programs provide supports or undertake environmental changes to help students graduate

Create environments that support learning, for example:

- School breakfast programs offer students a nutritious breakfast at school

- School-based health centers provide attending students health care services on school premises

- School-based social and emotional instruction efforts help kids recognize and manage emotions, set and reach goals, appreciate others’ perspectives, and maintain relationships

- School-based violence and bullying prevention programs address students’ disruptive and antisocial behavior through skill building

- Trauma-informed schools use a multi-tiered approach to address the needs of trauma-exposed youth

Increase education beyond high school, for example:

- College access programs help underrepresented students prepare academically, complete applications, and enroll

- Health career recruitment for minority students helps train and prepare for careers in health fields

Spokane County, WA, 2014

In Spokane, Washington, a 2014 RWJF Culture of Health Prize winner, a multi-pronged effort was launched to raise the science, technology, engineering, and mathematic abilities of students through mentoring, internships, and project-based learning. Learn more

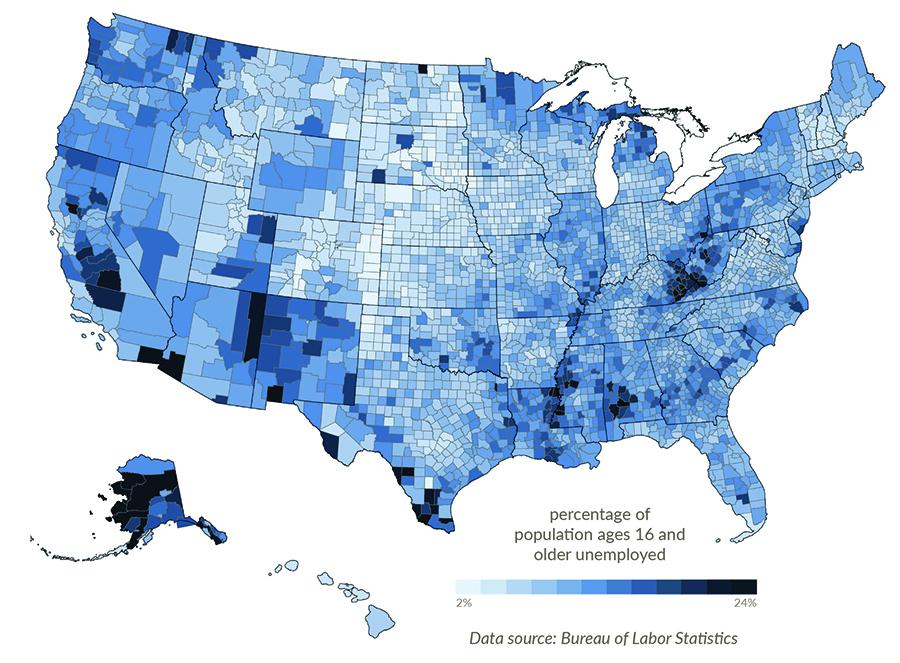

A Look at Income and Employment

Employment provides income and, often, benefits—such as paid sick leave—that can support healthy lifestyle choices. Unemployment limits these choices and negatively affects both quality of life and health overall. Across the U.S., there are large gaps in employment and income between people who live in the least healthy counties and those in the healthiest counties. Often, for American Indian/Alaskan Native, Black, and Hispanic people, barriers to opportunities for employment or higher income create gaps within communities that are similar, if not greater. Employers, educational institutions, and community members can work together to increase job skills for residents and enhance local employment opportunities.

What’s Working to Increase Income and Employment?

Examples of approaches and strategies with strong evidence of effectiveness to successfully reach these goals include:

Increase worker employability, for example:

- Adult vocational training programs support acquisition of job-specific skills through education or on-the-job training

- Career pathways and sector-focused employment programs provide occupation-specific training and supportive services in high-growth industries and sectors

- General Education Development (GED) certificate programs help those without a high school diploma achieve a GED

- Transitional jobs establish time-limited, subsidized, paid job opportunities to provide a bridge to unsubsidized employment

Create supportive work environments, for example:

- Paid family leave provides employees with paid time off for circumstances such as birth, adoption, or caring for family member with a serious medical condition

- Paid sick leave laws require employers to provide paid time off for employees when ill or injured

Increase or supplement income, for example:

- Child care subsidies that provide financial assistance to working parents, or parents attending school, to pay for center-based or certified in-home child care

- Expand refundable earned income tax credits for low to moderate income working families and adults

- Living wage laws establish locally-mandated wages that are higher than federal and state minimum wage levels

Support asset development, for example:

- Children’s development accounts build savings and assets over time with contributions from family, friends, and supporting organizations

- Matched dollar incentives for saving tax refunds build savings for low or moderate income individuals

Durham, NC, 2014

In Durham County, North Carolina, a 2014 RWJF Culture of Health Prize community, the Holton Career and Resource Center houses a virtual high school with onsite mentoring and a career center that exposes students to careers ranging from cosmetology to computer engineering. Learn more

In Durham County, North Carolina, a 2014 RWJF Culture of Health Prize community, the Holton Career and Resource Center houses a virtual high school with onsite mentoring and a career center that exposes students to careers ranging from cosmetology to computer engineering. Learn more

A Look at Family and Social Support

Social support stems from relationships with family members, friends, colleagues, and acquaintances. Social capital refers to those aspects of society that help us to create beneficial relationships and networks in a community, such as interpersonal trust and civic associations. People with greater social support, less isolation, and greater interpersonal trust live longer and healthier lives than those who are socially isolated. Communities richer in social connections provide residents with greater access to support and resources than those that are less tightly knit. Non-profit organizations, governments, health care, public health and community members can build and sustain partnerships that reflect the diversity of the community and work together to implement strategies that increase social connections and supports.

What’s Working to Build Family and Social Support?

Examples of approaches and strategies with strong evidence of effectiveness that communities can implement to improve social support and connectedness include:

Ensure access to counseling and support, for example:

- Employee Assistance Programs provide confidential worksite-based counseling and referrals to employees to address personal and workplace challenges

- Mental Health First Aid provides an 8- or 12-hour training to educate laypeople about how to assist individuals with, or at risk for, mental health problems

- Social service integration efforts coordinate access to services across multiple delivery systems

Increase social connectedness, for example:

- Extracurricular activities for social engagement offer social, art, or physical activities for school-aged youth outside of the school day

- Intergenerational mentoring establishes relationships between older adults and children or adolescents

- Youth peer mentoring establishes ongoing relationships between an older youth or young adult and a younger child or adolescent

Build social capital within communities, for example:

- Community centers facilitate local residents’ efforts to socialize, participate in recreational or educational activities, gain information, and seek support services

- Trauma-informed approaches to community building support and strengthen traumatized and distressed residents and address effects of trauma

Build social capital within families, for example:

- Early childhood home visiting programs provide expectant parents and families with young children with information, support, and training

- Father involvement programs support fathers’ active involvement in child rearing via various father- or family- focused interventions

Waaswaaganing Anishinaabeg (Lac Du Flambeau) Tribe, WI, 2015

In Waaswaaganing Anishinaabeg, a 2015 RWJF Culture of Health Prize community, family support and fostering cross-generational connections are priority through the program Cooking with Grandmas where community elders teach youth the “Ojibwe way.” Perhaps no other innovation embodies what is taking place in Waaswaaganing Anishinaabeg (Lac du Flambeau,WI), better than Envision. Though still in its infancy, this youth-driven learning program bridges generations while conveying life skills that do not fit neatly into any academic category. Envision immerses middle school students in the Ojibwe culture. Using traditional tribal methodologies, youth considered at risk are redirected, often with the gentle guidance of community leaders and elders. Learn more

In Waaswaaganing Anishinaabeg, a 2015 RWJF Culture of Health Prize community, family support and fostering cross-generational connections are priority through the program Cooking with Grandmas where community elders teach youth the “Ojibwe way.” Perhaps no other innovation embodies what is taking place in Waaswaaganing Anishinaabeg (Lac du Flambeau,WI), better than Envision. Though still in its infancy, this youth-driven learning program bridges generations while conveying life skills that do not fit neatly into any academic category. Envision immerses middle school students in the Ojibwe culture. Using traditional tribal methodologies, youth considered at risk are redirected, often with the gentle guidance of community leaders and elders. Learn more

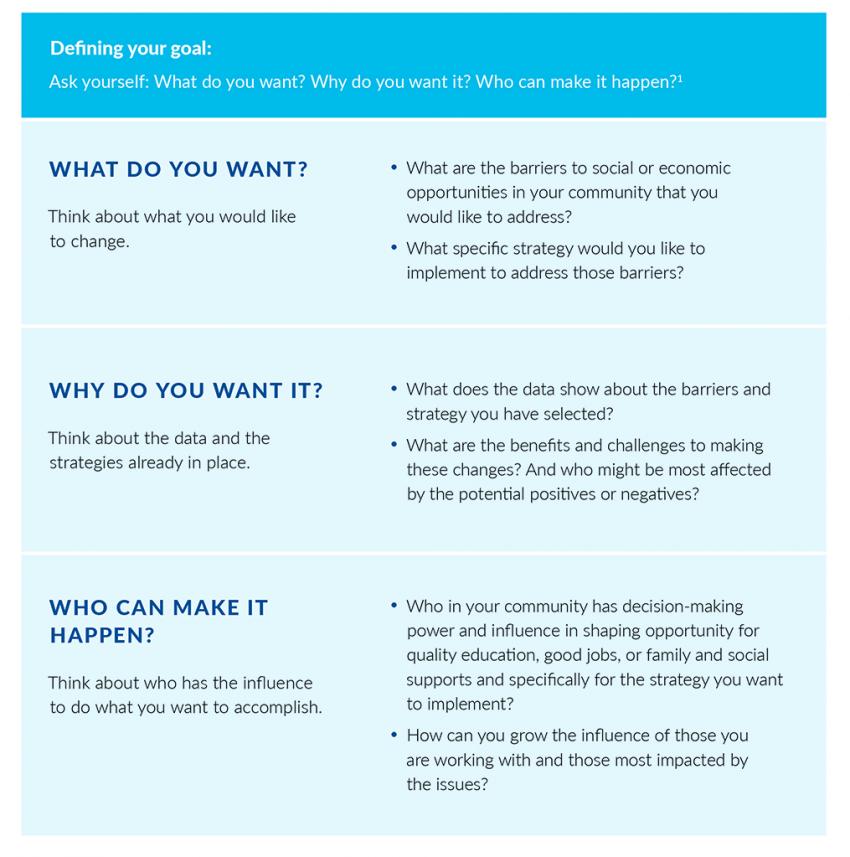

Choosing the Right Strategy for Your Community

Now What?

Once you have decided what you want to do, the next step is to make it happen. CHR&R’s guide to Act on What’s Important can help your community build on strengths, leverage available resources, and respond to unique needs.

This report provides examples of strategies that have been shown to make a difference in improving social and economic factors, especially for those who face barriers to opportunity. Visit What Works for Health to learn more about the specific outcomes and health factors each strategy has been shown to affect, and the decision makers who can help move it forward. This will help you develop your own short list of potential strategies.

As you explore strategies that may be a good fit for your community, be sure to:

- Consider the context: Strategies, even those that are rated Scientifically Supported, may not be right for every community. To evaluate whether a strategy might work where you are, ask yourself:

- Is the strategy a good fit for our community and our partners?

- Have we included those most affected by poor health or poor social and economic conditions in choosing the strategy?

- Is our community ready and able to support our chosen strategy? Do we have what we need to implement and evaluate the strategy?

-Does our community’s political environment support our strategy? - Consider the community: Communities are not always ready for change. It’s important to consider your community’s unique makeup, characteristics, and culture. Involving community residents along the way can help build support for change.

- Consider your stakeholders: Stakeholders are people who care about your issue. Often when we think of the political environment, we think of key decision makers. They’re important, but it is equally important to consider all stakeholder groups, including:

- The public. All those with vested interests. This might include community residents (particularly those who face barriers to opportunity and good health), advocacy groups, non-profit agencies, and businesses.

-Specific political stakeholders. Those who have the power to give you what you want, including elected and appointed officials or lobbying groups.

-Implementers. Those tasked with making the strategy work, such as administrators. This is an important group – a strategy only works when it’s implemented or enforced. - Select the best strategy: As you make your selection, consider a balance of strategies. Start with short-term strategies that give you early wins. At the same time, lay the groundwork for strategies that have a longer-term impact.

-Generate a list of your top choices. (This is a good time to look back at WWFH)

-Check your inclusiveness — have you engaged those most impacted by the issue?

-Choose a strategy — pull together what you know about your top choices, their impact, and your community to make a decision. - Consider whether to adapt the strategy: Policies and programs may not be a fit for your community straight “out of the box.” You may need to adjust the strategy to fit your community’s needs. If you do, be ready to conduct more rigorous evaluation to make sure it is working as intended.

Learn More about Social and Economic Strategies

The following tables provide more detail on strategies that can improve the social and economic factors that influence our communities. For each strategy, you will find an evidence rating (e.g., Scientifically Supported, Some Evidence) and decision makers who can help move the strategy forward. WWFH is updated regularly. To see the most current listings and learn more about these and other strategies that can make a difference in your community vist countyhealthrankings.org/whatworks.

Moving to Action

Having trouble getting started? This may be a good time to ask some simple questions that can guide the next steps of your work. You and your partners can begin by:

1 Reference: Power Prism® - Answering the Three Key Questions, M+R Strategic Services New England Office, www.powerprism.org

Columbia Gorge Region, OR & WA, 2016

In the Columbia Gorge region, a 2016 RWJF Culture of Health Prize winner, community health workers connect residents to helpful services and resources as well as provide parenting support and education. Learn more

Making Change

Guidance and Tools

Visit CHR&R’s Action Center to find step-by-step guidance and tools to help assess your needs, drive local policy and systems changes, and evaluate the impacts of health improvement efforts.

The way we go about making change in our community matters. Putting policies and systems in place that create social and economic opportunity for all requires attention to who may benefit or be harmed, and consideration of long-term implications. Be sure to:

- Engage a variety of stakeholders. Harnessing the collective power of local leaders, partners, and community members—including those who experience poor conditions for good health—is key to making change. Ensuring that everyone has a say in your community health improvement work can help to close gaps in health outcomes and improve health for all.

- Build strategic partnerships. Building meaningful connections across organizations and networks that care about health and equity can strengthen the capacity within your community to make change and support short- and long-term wins. Visit CHR&R’s Partner Center to help you identify and engage the right partners.

- Communicate. Consider how you will get your most important messages to the people who influence your goals. What you say and how you say it can motivate people to take action when you need it.

Technical Notes and Glossary of Terms

What is health equity? What are health disparities? And how do they relate?

Health equity means that everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible. This requires removing obstacles to health, such as poverty and discrimination, and their consequences, including powerlessness and lack of access to good jobs with fair pay, quality education and housing, safe environments, and health care.

Health disparities are differences in health or in the key determinants of health—such as education, safe housing, and discrimination—which adversely affect marginalized or excluded groups.

Health equity and health disparities are closely related to each other. Health equity is the ethical and human rights principle or value that motivates us to eliminate health disparities. Reducing and ultimately eliminating disparities in health and determinants of health is how we measure progress toward achieving health equity.

Braveman P, Arkin E, Orleans T, Proctor D, and Plough A. What is Health Equity? And What Difference Does a Definition Make? Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. May 2017

How did we select strategies to include in this report?

We selected strategies from the Social and Economic Factors section of What Works for Health based on those assigned the highest evidence of effectiveness ratings: Scientifically Supported, Some Evidence, and Expert Opinion. The availability of evidence about the effectiveness of strategies varies by topic. For example, there is much stronger evidence about the effectiveness of educational interventions than for employment and income-related interventions. Among this set of strategies, preference was given to those where there is scientific support (with consistently favorable results in robust studies) and favorable disparity ratings (see below). Preference was also given to broader strategies versus specific named programs, programs that can be implemented locally, and those that can be described and understood easily. The report also sought a balance in representation across the different approaches to improving social and economic opportunity, such as increasing early childhood education and increasing high school graduation. This report reflects content as of August 14, 2018.

WWFH Disparity Ratings

As WWFH evidence analysts review the available evidence on individual strategies, they assess each strategy’s likely effect on racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, and geographic disparities based on the best available evidence related to disparities in health outcomes and the strategy’s characteristics (e.g., target population, mode of delivery, cultural considerations). Strategies are rated:

- Likely to decrease disparities

- No impact on disparities likely

- Likely to increase disparities

Strategies that are likely to reduce differences in health outcomes (i.e., close a gap) are rated ‘Likely to decrease disparities,’ while strategies likely to increase differences are rated ‘Likely to increase disparities.’ Strategies that generally benefit entire populations are rated ‘No impact on disparities likely.’

To learn more about evidence analysis methods and evidence-informed strategies that can improve health for all, visit What Works for Health: countyhealthrankings.org/whatworks.

Credits

Recommended citation

University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute.

What Works? Social and Economic Opportunities to Improve Health for All.

September 2018.

Lead Authors

Marjory Givens, PhD, MSPH

Alison Bergum, MPA

Julie Willems Van Dijk, PhD, RN, FAAN

This publication would not have been possible without the following contributions:

Research Assistance

Lael Grigg, MPA

Bomi Kim Hirsch, PhD

Jessica Rubenstein, MPA, MPH

Jessica Solcz, MPH

Kiersten Frobom

Amanda Jovaag, MS

Keith Gennuso, PhD

Courtney Blomme, RD

Elizabeth Pollock, PhD

Joanna Reale

Matthew Rodock, MPH

Anne Roubal, PhD

Communications and Website Development

Kim Linsenmayer, MPA

Matthew Call

Lindsay Garber, MPA

Komal Dasani, MPH

Jennifer Robinson

Bridget Catlin, PhD, MHSA

Burness

Forum One

Funding provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation